The Spin Doctor Europadisc's Weekly Column

In praise of... Saint-Saëns

14th December 2021

14th December 2021

This week marks the centenary of the death of Camille Saint-Saëns (9 October 1835–16 December 1921), one of the giants of French 19th-century music. A child prodigy, piano and organ virtuoso and polymath (among his passionate interests beside music were the French, Greek and Latin classics, and the natural sciences including astronomy), he was a prolific composer steeped in the Viennese tradition but also a passionate champion of French music both new and old. Renowned for his versatility and natural musical giftedness, Saint-Saëns enjoyed a long career that stretched from early Romanticism (early admirers included Berlioz) to the dawn of modernism (he pronounced Stravinsky insane on hearing the first concert performance of Le Sacre du printemps in 1914, outlived Debussy by more than three years, and died when Berg’s Wozzeck was nearly completed). By the end of his life he had achieved not only worldwide fame but also a not entirely deserved reputation for representing the conservative old guard.

This week marks the centenary of the death of Camille Saint-Saëns (9 October 1835–16 December 1921), one of the giants of French 19th-century music. A child prodigy, piano and organ virtuoso and polymath (among his passionate interests beside music were the French, Greek and Latin classics, and the natural sciences including astronomy), he was a prolific composer steeped in the Viennese tradition but also a passionate champion of French music both new and old. Renowned for his versatility and natural musical giftedness, Saint-Saëns enjoyed a long career that stretched from early Romanticism (early admirers included Berlioz) to the dawn of modernism (he pronounced Stravinsky insane on hearing the first concert performance of Le Sacre du printemps in 1914, outlived Debussy by more than three years, and died when Berg’s Wozzeck was nearly completed). By the end of his life he had achieved not only worldwide fame but also a not entirely deserved reputation for representing the conservative old guard.You might think that Saint-Saëns hardly needs championing these days: his magnificently satirical Carnival of the Animals, the Danse macabre, the ‘Organ’ Symphony and Introduction et Rondo capriccioso have been staples of the repertoire for the past century, as have several of his concertos. Yet the very ubiquity of these works has often overshadowed his wider output and achievements. To have composed a handful of perennial hits is itself no mean feat, but behind them lies an output that encompasses all the major genres of 19th-century music, from opera, ballet and oratorio, via symphonies, concertos and symphonic poems, to chamber music, sonatas, solo piano works and an extensive list of songs, many of them on texts by Victor Hugo.

Surviving the early loss of his father and an early brush with tuberculosis, the Parisian-born Camille was playing the piano by the age of 3 under the tutelage of his great aunt, and by the time he was ten made his public debut at the Salle Pleyel in Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto and Mozart’s B flat Concerto, K450 (for which he wrote his own cadenza!). A crucial factor in ensuring that he didn’t become just another five-minute Wunderkind was his composition schooling with Pierre Maleden (a pupil of Fétis and Gottfried Weber), which grounded his training in classicism. (In 1848 he enrolled at the Paris Conservatoire, eventually joined the composition class of Fromental Halévy, himself a pupil of Cherubini.) Likewise, Saint-Saëns’s surprisingly broad cultural interests helped him develop a style that was notable for its eclecticism and accomplished craftsmanship rather than its originality, absorbing and refining an enviably wide variety of influences.

These included a strong admiration for Wagner, whose Tannhäuser and Lohengrin he championed in his writing when they were looked on by many French critics with scorn, and similarly the music of Schumann. Liszt, meanwhile, was a notable source of encouragement, admiring Saint-Saëns’s piano playing and composition and, on hearing the Frenchman play in La Madeleine (where he was organist for nearly twenty years from 1858) hailing him has the greatest organist in the world. The influence of Liszt can be felt in the four symphonic poems of the 1870s – including the 1874 orchestra-only version of his song Danse macabre as well as the classically-themed Rouet d'Omphale (1871), Phaéton (1873), and La Jeunesse d'Hercule (1877) – but with Gallic grace replacing Lisztian bombast. As early as his Second Symphony (1859) he had jettisoned the rather ponderous style and textures of his earlier orchestral works in favour of greater textural and motivic economy as well as the cyclic unity that found its most famous expression in the grandiose ‘Organ’ Symphony of 1886.

Yet for all the obvious debts Saint-Saëns owed to the Austro-German tradition, which continued right up to his late chamber works (all in ‘classical’ forms), it was his relationship with the music of his own country that was central to his creativity. His ‘rediscovery’ of the 17th-century clavecinistes as part of his ongoing musicological work (like Brahms, he was a prolific editor of old music) influenced his own later neoclassical developments. And the leading role he played in establishing the Société Nationale de Musique in the aftermath of the disastrous Franco-Prussian War was crucial in establishing a distinct identity for French music in the late 19th century, not least through the output of Gabriel Fauré, his lifelong friend and erstwhile pupil at the Ecole Niedermeyer. Even the exoticism that colours so many of his works, from the Spanish-infused Introduction et Rondo capriccioso (1863) and Havanaise (1887) to the Japonism of his 1872 opera La Princesse jaune and the north African favours of the Suite algérienne (1880), the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra Africa (1891) and the Fifth Piano Concerto (1896), can be viewed in the context of the French fascination with all things exotic, born of 19th-century colonialism.

Of Saint-Saëns’s 12 operas, only one – the marvellously atmospheric Biblical tale of Samson et Dalila (1877) – entered the repertoire, somewhat ironically given that it started life as an oratorio (and was performed as such when he conducted it at Covent Garden in 1893 thanks to the squeamishness of the Victorian censors). His other works in the genre are dramatically flawed but contain so much beautifully crafted and engaging music that their recent re-emergence on disc is hugely welcome. The chamber music, long beloved of players but regarded with disdain by academics, is also long overdue reassessment, while the songs and the solo piano music are ripe for further exploration in concert and in the studios.

Perhaps Saint-Saëns’s greatest achievement – alongside his determination to raise the profile of French music – was the groundwork he laid in his later years (particularly with his pioneering woodwind sonatas of 1921 with their spare lines and elegant design) for the French Neoclassicism of the 1920s onwards. They are part of the huge legacy left by a composer who grew up in the shadow of Meyerbeer and Halévy, but who went on to write a cantata in praise of electricity (Le Feu celeste) for the Exposition Universelle of 1900, and who witnessed (with evidently mixed feelings!) the rise of musical Impressionism and Modernism, while forging his own distinct path, constantly refining and adapting tradition rather than rejecting it.

A few suggested recordings:

Camille Saint-Saëns Edition (34 CDs, various artists, incl. historic performances) 9029674604

Symphonies (ORTF/Martinon) 0852052 or 5851862

Piano Concertos (Hough, CBSO/Oramo) CDA673312

Piano Concertos 2 & 5 (Chamayou, Orchestre National de France/Krivine) 9029563426

Violin Concertos (Graffin, BBC Scottish SO/Brabbins) CDA67074

Violin Concerto no.3, etc. (Kantorow, Tapiola Sinfonietta/ Bakels) BISCD1470

Cello Concertos (Clein, BBC Scottish SO/Manze) CDA68002

Symphonic Poems (Orchestre National de Lille/Märkl) 8573745

Chamber Music incl. woodwind sonatas (Nash Ensemble) CDA674312

Piano Trios (Florestan Trio) CDA67538

Samson et Dalila (Bouvier, Luccioni, Paris Opéra/Fourestier) 811006364 [historic recording from 1946, but the most unmistakably French recording of all, blazingly committed]

Le Timbre d’argent (Devos, Christoyannis, Les Siècles/FX Roth) BZ1041

Songs (F Le Roux, G Johnson) CDA66856

Piano Works, Paraphrases & Transcriptions (Anthony Gray) DDA21235 & DDA21236 [first two volumes of a new survey]

Latest Posts

Return to Finland: Rautavaara, Saariaho & Beyond

17th April 2024

Our previous visits to the music of Finland took us up to those composers born in the first decades of the 20th century, including Uuno Klami and Joonas Kokkonen. That generation brought Finnish music further away from its nationalist roots and the shadow of Sibelius, and closer to the modernism of the mid- and late 20th century. Now, on our final visit (at least for the time being), we look at two figures in particular who tackled some of modernism’s most advanced trends, and went beyond them to create outputs of... read more

read more

Classical Music: The Endgame?

10th April 2024

A recent visit to the London Coliseum brought home the scale of the challenge facing opera, not just at the home of the troubled English National Opera, but more generally – and, indeed, classical music more widely. What seemed to be a fairly respectable attandance was revealed – on a glance upwards to the upper circle and balcony – to be only half a house: the upper levels were completely empty, having been effectively closed from sale. And this on a Saturday evening! There was a time (in the 1970s and 80s) when... read more

read more

Artists in Focus: Masaaki Suzuki and the Bach Collegium Japan

3rd April 2024

Over the past three decades, the record catalogues have welcomed three landmark cycles of the complete Bach cantatas. John Eliot Gardiner’s survey of the complete sacred cantatas, made in a single year during his 2000 Bach Cantata Pilgrimage, grabbed most of the headlines. But the more long-term projects of Ton Koopman and Masaaki Suzuki (the latter with his Bach Collegium Japan) have their devotees, particularly among those who appreciate a more considered, patient approach in this music. Suzuki’s cycle in particular – the... read more

read more

Valete: Pollini, Eötvös & Janis

27th March 2024

The past fortnight has brought news of the deaths of three major figures from the post-war musical scene: two pianists and a composer-conductor.

Anyone who follows the classical music headlines even slightly will have learned of the death at the age of 82 of Maurizio Pollini. He was simply one of the greatest pianists of the post-war era. Born on 5 January 1942 in Milan, he was raised in a home environment rich in culture. His father Gino was a leading modern architect, his mother Renata Melotti a pianist, and her... read more

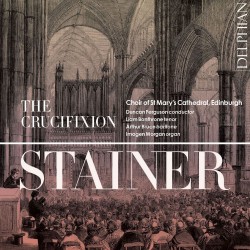

The Resurrection of Stainer’s ‘Crucifixion’

20th March 2024

Widely vilified as the epitome of mawkish late-Victorian religious sentimentality, John Stainer’s The Crucifixion was first performed in St Marylebone Parish Church on 24 February 1887 at the beginning of Lent. Composed as a Passion-themed work within the capabilities of parish choirs as part of the Anglo-Catholic revival, its publication by Novello led to its phenomenal success as churches throughout England quickly took it up. It also spawned many imitations – such as John Henry Maunder’s Olivet to Calvary – which lacked... read more

read more FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!