The Spin Doctor Europadisc's Weekly Column

Insight or idiosyncrasy? The art of 'underlining'

18th August 2021

18th August 2021

In 1886 Brahms wrote to his close associate the violinist Joseph Joachim, who was preparing to conduct an early performance of Brahms’s Fourth Symphony in Berlin: ‘I have marked a few tempo modifications in the score with pencil. They may be useful, even necessary, for the first performance .... Such exaggerations are only necessary where a composition is unfamiliar to an orchestra or soloist .... Once a work has become part of [the musicians’] flesh and blood, then in my opinion nothing of that sort is justifiable any more.’ In the days before recordings made new repertoire familiar not just to musicians but to audiences as well, and when the only opportunity of really getting to know works was on the occasion of (relatively rare) live performance, such exaggerations – slowings down, accelerations, but also dynamic tweaks and highlighting – were common practice when introducing new works to the repertoire. After the pieces had ‘bedded down’, such modifications were (at least in Brahms’s view) no longer ‘necessary’ or ‘justifiable’.

In 1886 Brahms wrote to his close associate the violinist Joseph Joachim, who was preparing to conduct an early performance of Brahms’s Fourth Symphony in Berlin: ‘I have marked a few tempo modifications in the score with pencil. They may be useful, even necessary, for the first performance .... Such exaggerations are only necessary where a composition is unfamiliar to an orchestra or soloist .... Once a work has become part of [the musicians’] flesh and blood, then in my opinion nothing of that sort is justifiable any more.’ In the days before recordings made new repertoire familiar not just to musicians but to audiences as well, and when the only opportunity of really getting to know works was on the occasion of (relatively rare) live performance, such exaggerations – slowings down, accelerations, but also dynamic tweaks and highlighting – were common practice when introducing new works to the repertoire. After the pieces had ‘bedded down’, such modifications were (at least in Brahms’s view) no longer ‘necessary’ or ‘justifiable’.More than 130 years on, and with a century or more of recordings making the ‘core repertoire’ or ‘canon’ – subtly shifting with time as it does – familiar to an ever greater number of listeners, we may be in the opposite position. Familiarity may breed, if not exactly contempt, then a certain ennui that introduces the danger of musical complacency. The range of interpretative parameters, when compared with the days of the earliest recordings, appears to have shrunk, with the arrival of recordings to tape in the 1940s, the arrival of the long playing record and stereo in the 1950s, and the dawn of digital recording and the compact disc in the 1980s, all introducing a perfectionism and standardisation in performance that was in danger of sucking the life out of musical performance even as it became more vividly reproducible for the home listener.

There have, however, always been musicians for whom the art of ‘underlining’ – the exaggeration of tempo extremes, phrasing and dynamics, to say nothing of the expressive impact – has been almost second nature. The pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow was a notable exponent of such an approach in the later 19th century. Within recent memory, Leonard Bernstein was a master of the art, daring to go against the consensus of good musical ‘taste’ and knowing how to squeeze out every last drop of emotion from a piece to heighten its effectiveness, while retaining a strong sense of its architecture. Others of a more eccentric bent (Sergiu Celibidache, particularly in his later years, and the controversial Giuseppe Sinopoli) had more variable levels of success.

The formidable attention to detail of musicians such as conductors Simon Rattle and Robin Ticciati is well-known to critics and audiences, though their micro-tweaking often comes at the expense of the overall musical architecture. Nor are conductors the only ones to indulge in such forms of expressive highlighting. The great Canadian pianist Glenn Gould, who limited his later performances to the recording studio where he could attain the maximum possible musical intensity and concentration, is a particularly famous example. More recently the maverick violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja has made her reputation not just with a dazzling technique, but also with a hefty dose of iconoclasm when tackling canonical works from Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto or Ravel’s Tzigane to Schoenberg's Sprechgesang masterpiece Pierrot lunaire (a remarkable vocal performance which will have alarmed as many listeners as it excited).

Nowhere has this tendency towards ‘underlining’ been more evident than in the field of ‘period’ or ‘historically informed’ performance. Here the grand master was Nikolaus Harnoncourt, whose performances, from his often rough-and-ready but also extraordinarily vivid early performances of Bach and his Baroque forbears to his later excursions into Mozart and Beethoven symphonies, dared to introduce ideas and expressive strategies that were thought de trop by many experts (his introduction of unwritten agogic pauses in Mozart’s ‘Jupiter’ and Beethoven’s Fifth in particular raised the hackles of the crustier critics). Alongside such daringly rethought performances, the squeaky-clean performances of other members of the early music brigade seemed to pale somewhat.

Among Harnoncourt’s musical successors are René Jacobs, whose cycle of Mozart operas for the French label Harmonia Mundi, raised the bar for musical interventionism, particularly in the dazzlingly imaginative realisation of the recitatives, Hervé Niquet with Le Concert Spirituel, and most recently the Greek conductor Teodor Currentzis, whose own cycle of Mozart’s ‘Da Ponte’ operas was even bolder in its flights of fancy while simultaneously phenomenally virtuosic, the product of many hours of fastidious detailed rehearsal. His recently launched cycle of Beethoven symphonies (so far only the Fifth and Seventh are available) looks set to raise the bar of period-style micro-management even further; undeniably exciting in its results, this style of closely rehearsed and minutely controlled performance is once again exercising the arbiters of musical good taste.

Perhaps the most striking example of such musical idiosyncrasy is in the field of a cappella vocal music. With tonal and expressive perfectionism in recent decades reaching hitherto unknown levels (think of the Tallis Scholars, The Sixteen, Gothic Voices, Les Arts Florissants and La Compagnia del Madrigale, to name just a very few), the wildcards are definitely Graindelavoix under the eccentric but brilliant direction of Björn Schmelzer. The medieval and Renaissance repertoire on which they focus may necessarily be more speculative in matters of performance than Brahms or Ravel, but what has been dubbed (often unkindly) their ‘Corsican goatherd’ style of singing has consistently shone new light not just on obscure corners of the repertoire, but on such early masterpieces as Guillaume de Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame and Carlo Gesualdo’s emotionally intense Tenebrae Responsories.

From Bernstein to PatKop, Harnoncourt to Graindelavoix, these musical mavericks who have dared to reclaim the art of ‘underlining’ and taken it to the sort of extremes which Brahms (himself considered an expert in early music in his day) can scarcely have imagined or intended, do us an immense service in preventing vast swaths of repertoire from going stale. In the best cases, the freshness they introduce can inspire new generations of performers, composers and listeners; they deserve to be heard even by the most diehard traditionalists.

A few recommendations:

Mahler - Symphony no.5 (Leonard Bernstein, Wiener Philharmoniker) 4776334

Mozart - Don Giovanni (René Jacobs, Freiburger Barockorchester) HMC90196466

Tchaikovsky - Violin Concerto (Patricia Kopatchinskaja, Teodor Currentzis) 88875190402

Schoenberg - Pierrot lunaire, etc. (Patricia Kopatchinskaja) ALPHA722

Machaut - Messe de Nostre Dame (Schmelzer, Graindelavoix) GCDP32110

Suggested reading:

Robert Philip: Performing Music in the Age of Recording (Yale University Press, 2004) [from which the Brahms quote is taken)

Latest Posts

Classical Music: The Endgame?

10th April 2024

A recent visit to the London Coliseum brought home the scale of the challenge facing opera, not just at the home of the troubled English National Opera, but more generally – and, indeed, classical music more widely. What seemed to be a fairly respectable attandance was revealed – on a glance upwards to the upper circle and balcony – to be only half a house: the upper levels were completely empty, having been effectively closed from sale. And this on a Saturday evening! There was a time (in the 1970s and 80s) when... read more

read more

Artists in Focus: Masaaki Suzuki and the Bach Collegium Japan

3rd April 2024

Over the past three decades, the record catalogues have welcomed three landmark cycles of the complete Bach cantatas. John Eliot Gardiner’s survey of the complete sacred cantatas, made in a single year during his 2000 Bach Cantata Pilgrimage, grabbed most of the headlines. But the more long-term projects of Ton Koopman and Masaaki Suzuki (the latter with his Bach Collegium Japan) have their devotees, particularly among those who appreciate a more considered, patient approach in this music. Suzuki’s cycle in particular – the... read more

read more

Valete: Pollini, Eötvös & Janis

27th March 2024

The past fortnight has brought news of the deaths of three major figures from the post-war musical scene: two pianists and a composer-conductor.

Anyone who follows the classical music headlines even slightly will have learned of the death at the age of 82 of Maurizio Pollini. He was simply one of the greatest pianists of the post-war era. Born on 5 January 1942 in Milan, he was raised in a home environment rich in culture. His father Gino was a leading modern architect, his mother Renata Melotti a pianist, and her... read more

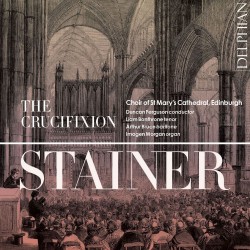

The Resurrection of Stainer’s ‘Crucifixion’

20th March 2024

Widely vilified as the epitome of mawkish late-Victorian religious sentimentality, John Stainer’s The Crucifixion was first performed in St Marylebone Parish Church on 24 February 1887 at the beginning of Lent. Composed as a Passion-themed work within the capabilities of parish choirs as part of the Anglo-Catholic revival, its publication by Novello led to its phenomenal success as churches throughout England quickly took it up. It also spawned many imitations – such as John Henry Maunder’s Olivet to Calvary – which lacked... read more

read more

Label News: Chandos goes to Naxos

14th March 2024

With the recently announced acquisition of Chandos Records by the founder of Naxos Records, Klaus Heymann, another leading independent classical label has passed to a larger company. Just last year, both the Swedish label BIS and the British firm Hyperion were snapped up, by Apple Music and Universal Music respectively. The press release issued to confirm the situation with Chandos spoke of a ‘synergy’ between Chandos and Heymann’s team, and stressed that ‘the label will remain independent long-term’. Chandos is... read more

read more FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!