The Spin Doctor Europadisc's Weekly Column

Keeping the Politics out of it? Part 2: 19th-Century Musical Nationalism

5th October 2021

5th October 2021

The present-day desire to keep politics out of music is, as we have previously seen, something of a pipe dream when the long history of entanglement between the arts and power structures (sacred or secular) is considered. From its earliest roots in the Middle Ages, western classical music has constantly been at the service of church and state, a position which changed only cosmetically and by degree during the 18th-century Enlightenment and the early Classical era. The church’s influence may have waned over time, but the emergence of other power structures filled its place and – just at the moment that a mood of emancipation seemed to be in the air in the wake of the French Revolution, which so inspired Cherubini, Beethoven and their contemporaries – new realities (among them Napoleon Bonaparte’s usurpation of the revolutionary republic with a new empire) took hold.

The present-day desire to keep politics out of music is, as we have previously seen, something of a pipe dream when the long history of entanglement between the arts and power structures (sacred or secular) is considered. From its earliest roots in the Middle Ages, western classical music has constantly been at the service of church and state, a position which changed only cosmetically and by degree during the 18th-century Enlightenment and the early Classical era. The church’s influence may have waned over time, but the emergence of other power structures filled its place and – just at the moment that a mood of emancipation seemed to be in the air in the wake of the French Revolution, which so inspired Cherubini, Beethoven and their contemporaries – new realities (among them Napoleon Bonaparte’s usurpation of the revolutionary republic with a new empire) took hold.A time of hitherto unparalleled scientific and technical progress, the 19th century was also the age of nationalism. States had existed before, of course, be they city states, duchies, principalities, kingdoms, even empires and republics. But nation states, rooted in a national identity that was built not merely on ethnic, linguistic, geographical or cultural lines, but on a combination of such factors, some more elusive than others, are very much a 19th-century phenomenon. Even more so is ‘nationalism’, the invocation of a shared ‘national spirit’ that received its classic formulation by the German philosopher and theologian Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803), who saw a sense of national identity as rooted in a shared language. Herder’s ideas were enormously influential throughout the 19th century (as, later on, were those of Hegel), and the idea of a shared national identity took hold in German-speaking lands perhaps precisely because they were so fragmented along religious and political lines, even at a time when a dominant Prussia was beginning to flex its muscles.

Although the conventional view of musical nationalism has been to regard it as something rather exotic, the domain of smaller, peripheral nations struggling for independence or a sense of common identity, the search for a collective identity rooted in folk culture (however culturally mediated) is a particular feature of early German musical Romanticism, particularly in the domain of vernacular vocal music: the art-song (or Lied, with its folk-like and often folk-themed texts) and opera (Weber’s Der Freischütz and a host of imitators). Secular choruses for the many emerging urban choral societies, as well as Handelian-style oratorios such as Mendelssohn’s Paulus, also played a significant part in the liberal nationalism of the first half of the 19th century.

In the aftermath of the revolutionary events of 1848, however, German nationalism (both political and musical) took a rather different course, more exclusive and even overtly hostile to outside influences. Perhaps the best-known examples are Wagner’s epic Der Ring des Nibelungen, rooted in Norse folk myth but also in notions of racial ‘purity’, and his only comic opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, with its closing exhortation to honour German art. Together with Liszt, Wagner was the most prominent representative of the New German School, by that time diametrically opposed to the more conservative-leaning ‘pure instrumental music’ of Brahms and his acolyte, the Viennese music critic Eduard Hanslick. It’s a little surprising, then, to discover that one of the most unashamedly jingoistic choral works, written in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, is the Triumphlied by Brahms, composed for the largest collection of forces he ever wrote for, and a very different iteration of German-ness from his Ein deutsches Requiem of just a few years earlier.

It was France’s 1870 humiliation that also provided the catalyst for the foundation by Romain Bussine and Camille Saint-Saëns of the Société nationale de musique, which sought to foster a distinctively French musical identity chiefly in just the areas – chamber and instrumental music – where German composers were hitherto thought to excel. Among the works premiered by the society were César Franck’s Piano Quintet, Fauré’s Piano Quartets and La Bonne Chanson, but it took a while for it to shake off the earnestness of its earliest endeavours and achieve that clarity and lightness of touch which has since come to be regarded as quintessentially French.

In Italy, musical nationalism was inextricably bound up with the struggles for unity and independence of the Risorgimento, of which Verdi is often regarded as the leading musical exponent. Even if the now-mythic association of the chorus of the Hebrew slaves (‘Va, pensiero’) from his 1842 opera Nabucco has recently been shown to be a largely retrospective projection, the potency a memorable, noble melody intoned by unison chorus, used in his following operas, undoubtedly struck a chord (if that’s the right term) with his compatriots.

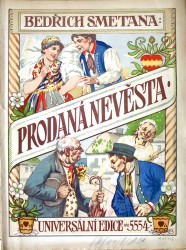

With its mixture of popular appeal and profound, passionate expressive content, as well as its ability to represent on stage moments of national myth or history, opera furnishes particularly powerful examples of musical nationalism. The ‘national composers’ of several nascent or resurgent nations were often those who were able to furnish them with operas befitting the stature to which their would-be citizens aspired. In Poland it was Moniuszko (not the émigré Fryderyk Chopin) with Halka, in Hungary Ferenc Erkel (rather than the Germanised Franz Liszt), and in the Czech Lands Smetana (above all with The Bartered Bride and Libuše) who occupied the top spots. The foundation of dedicated national theatres, in imitation of a trend that started in Germany, was a key part of this musical ‘nation-building’.

Opera was also a crucial part of musical nationalism in Russia, starting with Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar (1836) and reaching a high-point in the operas of Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, both members of the ‘Mighty Handful’ gathered around Mily Balakirev, who sought to create a more authentically Russian style of classical music independent of what was regarded as the western conservatoire tradition epitomised by Tchaikovsky. The extent to which they succeeded is still much debated, but should not blind us to the staggering originality of Mussorgsky’s contributions to the operatic genre in particular. In nations with less well-established operatic traditions, other genres served as substitute, such as the theatre music of Edvard Grieg and Jean Sibelius, while the latter’s frequent recourse to quasi-folk sources (like the Kalevala) of the earlier 19th century bring us back full-circle to the practices of German Romanticism.

- Richard Taruskin: ‘Nationalism’, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition (London: Macmillan, 2001)

- Carl Dahlhaus (trans. J. Bradford Robinson): Nineteenth-Century Music (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989)

Recommended listening:

Mendelssohn - Paulus CHAN105162X

Brahms - Triumphlied CHAN10165

Franck - Piano Quintet (+ Debussy - String Quartet) CDA68061

Verdi - Nabucco 2564648317

Moniuszko - Halka DUX8331 (DVD) / DUX6331 (Blu-ray)

Smetana - The Bartered Bride SU70119 (DVD), Libuše SU39822

Dvořák - Symphonic Poems SU40122

Erkel - King Stephen 866034546

Glinka - A Life for the Tsar ELQ4826924

Mussorgsky - Khovanshchina 109159 (DVD) / 109160 (Blu-ray)

Sibelius - Kullervo, Finlandia, etc. 6484032

Latest Posts

Remembering Sir Andrew Davis

24th April 2024

The death at the age of 80 of the conductor Sir Andrew Davis has robbed British music of one of its most ardent champions. Since the announcement of his death this weekend, numerous headlines have linked him with his many appearances at the helm of the BBC’s Last Night of the Proms, occasions which were enlivened by his lightly-worn bonhomie and mischievous wit. The Last Night, with its succession of patriotic favourites, was something that came naturally to Davis, as did an easy rapport with both his fellow musicians and... read more

read more

Return to Finland: Rautavaara, Saariaho & Beyond

17th April 2024

Our previous visits to the music of Finland took us up to those composers born in the first decades of the 20th century, including Uuno Klami and Joonas Kokkonen. That generation brought Finnish music further away from its nationalist roots and the shadow of Sibelius, and closer to the modernism of the mid- and late 20th century. Now, on our final visit (at least for the time being), we look at two figures in particular who tackled some of modernism’s most advanced trends, and went beyond them to create outputs of... read more

read more

Classical Music: The Endgame?

10th April 2024

A recent visit to the London Coliseum brought home the scale of the challenge facing opera, not just at the home of the troubled English National Opera, but more generally – and, indeed, classical music more widely. What seemed to be a fairly respectable attandance was revealed – on a glance upwards to the upper circle and balcony – to be only half a house: the upper levels were completely empty, having been effectively closed from sale. And this on a Saturday evening! There was a time (in the 1970s and 80s) when... read more

read more

Artists in Focus: Masaaki Suzuki and the Bach Collegium Japan

3rd April 2024

Over the past three decades, the record catalogues have welcomed three landmark cycles of the complete Bach cantatas. John Eliot Gardiner’s survey of the complete sacred cantatas, made in a single year during his 2000 Bach Cantata Pilgrimage, grabbed most of the headlines. But the more long-term projects of Ton Koopman and Masaaki Suzuki (the latter with his Bach Collegium Japan) have their devotees, particularly among those who appreciate a more considered, patient approach in this music. Suzuki’s cycle in particular – the... read more

read more

Valete: Pollini, Eötvös & Janis

27th March 2024

The past fortnight has brought news of the deaths of three major figures from the post-war musical scene: two pianists and a composer-conductor.

Anyone who follows the classical music headlines even slightly will have learned of the death at the age of 82 of Maurizio Pollini. He was simply one of the greatest pianists of the post-war era. Born on 5 January 1942 in Milan, he was raised in a home environment rich in culture. His father Gino was a leading modern architect, his mother Renata Melotti a pianist, and her... read more

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!