The Spin Doctor Europadisc's Weekly Column

The Misfits (Part 1 of 2)

1st June 2021

1st June 2021

It is, at least in the public imagination, the creative artist’s prerogative to be ‘different’. As with the ‘mad scientist’ of popular lore (Victor Frankenstein, Dr Jekyll...), the mad eccentricities of genius are the price to be paid for insights into the human condition and soul. In practice, the situation is rather more nuanced. Indeed, for most of the modern history of western culture, it has been the duty of artists to conform: to tailor their brilliance to the whims of patrons (the church, royalty, the nobility) and – since the opening up of ‘high culture’ to the bourgeois masses in the 19th century – to the changeable tastes of audiences. Few if any creative minds have made much progress in their profession without some sort of artistic compromise. Moreover, in music, as in other arts, we tend to think in terms of broad cultural periods – medieval, renaissance, baroque, classical, romantic, post-romantic – or of larger geographic locale – the French clavecinistes, Italian opera, the German romantic movement, and assorted nationalist trends. Yet throughout music history, since the middle ages, there have been those who stood on the margins of such convenient generalisations, through varying combinations of personal quirkiness and sheer force of artistic vision. Such outsiders, unrepresentative as they may be, are always tremendously rewarding to investigate, and often repay the effort of seeking them out many times over.

It is, at least in the public imagination, the creative artist’s prerogative to be ‘different’. As with the ‘mad scientist’ of popular lore (Victor Frankenstein, Dr Jekyll...), the mad eccentricities of genius are the price to be paid for insights into the human condition and soul. In practice, the situation is rather more nuanced. Indeed, for most of the modern history of western culture, it has been the duty of artists to conform: to tailor their brilliance to the whims of patrons (the church, royalty, the nobility) and – since the opening up of ‘high culture’ to the bourgeois masses in the 19th century – to the changeable tastes of audiences. Few if any creative minds have made much progress in their profession without some sort of artistic compromise. Moreover, in music, as in other arts, we tend to think in terms of broad cultural periods – medieval, renaissance, baroque, classical, romantic, post-romantic – or of larger geographic locale – the French clavecinistes, Italian opera, the German romantic movement, and assorted nationalist trends. Yet throughout music history, since the middle ages, there have been those who stood on the margins of such convenient generalisations, through varying combinations of personal quirkiness and sheer force of artistic vision. Such outsiders, unrepresentative as they may be, are always tremendously rewarding to investigate, and often repay the effort of seeking them out many times over.Latest Posts

Return to Finland: Rautavaara, Saariaho & Beyond

17th April 2024

Our previous visits to the music of Finland took us up to those composers born in the first decades of the 20th century, including Uuno Klami and Joonas Kokkonen. That generation brought Finnish music further away from its nationalist roots and the shadow of Sibelius, and closer to the modernism of the mid- and late 20th century. Now, on our final visit (at least for the time being), we look at two figures in particular who tackled some of modernism’s most advanced trends, and went beyond them to create outputs of... read more

read more

Classical Music: The Endgame?

10th April 2024

A recent visit to the London Coliseum brought home the scale of the challenge facing opera, not just at the home of the troubled English National Opera, but more generally – and, indeed, classical music more widely. What seemed to be a fairly respectable attandance was revealed – on a glance upwards to the upper circle and balcony – to be only half a house: the upper levels were completely empty, having been effectively closed from sale. And this on a Saturday evening! There was a time (in the 1970s and 80s) when... read more

read more

Artists in Focus: Masaaki Suzuki and the Bach Collegium Japan

3rd April 2024

Over the past three decades, the record catalogues have welcomed three landmark cycles of the complete Bach cantatas. John Eliot Gardiner’s survey of the complete sacred cantatas, made in a single year during his 2000 Bach Cantata Pilgrimage, grabbed most of the headlines. But the more long-term projects of Ton Koopman and Masaaki Suzuki (the latter with his Bach Collegium Japan) have their devotees, particularly among those who appreciate a more considered, patient approach in this music. Suzuki’s cycle in particular – the... read more

read more

Valete: Pollini, Eötvös & Janis

27th March 2024

The past fortnight has brought news of the deaths of three major figures from the post-war musical scene: two pianists and a composer-conductor.

Anyone who follows the classical music headlines even slightly will have learned of the death at the age of 82 of Maurizio Pollini. He was simply one of the greatest pianists of the post-war era. Born on 5 January 1942 in Milan, he was raised in a home environment rich in culture. His father Gino was a leading modern architect, his mother Renata Melotti a pianist, and her... read more

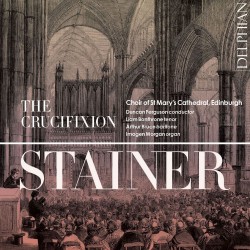

The Resurrection of Stainer’s ‘Crucifixion’

20th March 2024

Widely vilified as the epitome of mawkish late-Victorian religious sentimentality, John Stainer’s The Crucifixion was first performed in St Marylebone Parish Church on 24 February 1887 at the beginning of Lent. Composed as a Passion-themed work within the capabilities of parish choirs as part of the Anglo-Catholic revival, its publication by Novello led to its phenomenal success as churches throughout England quickly took it up. It also spawned many imitations – such as John Henry Maunder’s Olivet to Calvary – which lacked... read more

read more FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!