The Spin Doctor Europadisc's Weekly Column

When Music is Silenced

8th September 2021

8th September 2021

Thanks in large part to enterprising musicians, musicologists and record labels, many of those lost voices – even the ones extinguished so brutally in the gas chambers and gulags – have sounded again, with renewed potency, for new generations of audiences. Yet at the same time the terrible cycle of silencing goes on, and at this time in particular musicians in Afghanistan are being muted, their livelihoods and lives under threat as a result of the recent political and military turmoil. Once again, the Taliban are likely to stifle a musical culture that is noted for its vibrancy and resilience, its rich combination of tradition and innovation.

Just as Afghanistan itself straddles the intersection of Persian, Turkic and Hindustani culture, so Afghan music – classical, popular and traditional folk – reflects these influences, in sounds that have distinct regional identities, but which are also capable of cross-fertilisation. One of the most important features of Afghan music is the sung poetry known as the ghazal, a romance or ode constructed in rhyming couplets. Ghazals by great Afghan poets as well as Persians such as Hafez (1315–1390) are immensely popular in musical settings, particularly in the western, central and north-eastern belt of the country. In the Pashtun south-eastern regions, by contrast, the influence of Indian classical ragas is stronger, but with a greater emphasis on rhythmic variation, creating a lively style for which Afghan music is especially noted.

Of the many instruments, bowed, plucked and struck, the most quintessential is the rubab, a double-chambered, plucked and fretted lute which is regarded as the national instrument. The chief percussion instrument is the two-drum tabla familiar from Indian classical music, but there’s a great variety of other stringed instruments and percussion, both local and of Indian ancestry, to be heard (including the dilruba, sarod and dutar).

The instruments and styles of Afghan classical music (klasik) have also influenced the accompaniments to its vocal popular music, which also bears traces of folk traditions in which shawms and frame drums (daireh) play an important role (particularly with professional Roma musicians). In the capital, Kabul, the greatest talents in the classical genre are given the esteemed title of ustad, as in other Hindustani-influenced traditions; rural folk musicians, on the other hand, are regarded as very low in the traditional social pecking order.

Most of these musical activities – as well as the traditional gender-segregated performances at Afghan wedding parties – are now once again under threat, but it is particularly the participation of women in music that is likely to face the greatest censure and danger from the new authorities. In Kabul, the Afghan National Institute of Music has over the past six years undertaken a particularly bold initiative to create the country’s first all-women orchestra, ‘Zohra’, which combines Afghan and western instruments in a mixture of traditional-style and newly-composed works, and also has dedicated women conductors. In 2017 it played to ecstatic audiences on its first European tour, including performances at the World Economic Forum in Davos, offering a beacon of hope for a future that has, at least for now, been cruelly extinguished. Many of the orchestra’s members have managed to escape the country, some having already received death threats even before the recent turmoil, but the hope must surely be that it can be reconstituted in some form, even in exile.

Fortunately, several of Zohra’s tour performances can be viewed on YouTube, but it also entered a fruitful relationship with Australian-born composer Sadie Harrison, alongside musicians from Goldsmith’s College, London, and the American string sextet Cuatro Puntos. The results, including Harrison’s three-movement The Rosegarden of Light as well as some traditional Afghan items, can be heard on a fascinating 2016 disc on the Toccata label, notable for its infectious rhythms, evocative modal melodies and tremendously committed playing.

Further evidence of Sadie Harrison’s immersion in Afghan culture can be heard on an earlier disc from Metier (2003), including her own trilogy The Light Garden alongside traditional folk songs, with Ustad Asif Mahmoud on tabla joining several western Afghan music specialists plus the Lontano and Tate ensembles. Harrison’s music here has a tougher edge to it, but the joy is hearing it juxtaposed with such beguiling traditional repertoire. As with the Toccata disc, there are detailed, extensive and hugely helpful notes from experts Veronica Doubleday (the singer in two of the folk songs) and rubab player John Baily.

For their sensitive pairing of new compositions with traditional Afghan numbers, both these discs serve as fascinating entry points for listeners inclined to investigate this music in greater depth. At a time when musical culture and the musicians themselves – including the brave, pioneering young artists featured on the Toccata album – are under renewed threat, they deserve the widest possible currency, and will undoubtedly reward and enrich those who listen to them. Hold these artists in your thoughts, support their activities, and hope that Afghan music will rise again as it has before!

The recordings:

- Sadie Harrison - The Rosegarden of Light TOCC0342

- Sadie Harrison - The Light Garden Trilogy MSVCD92084

Further reading:

- Booklet notes to the above recordings

- Veronica Doubleday: ‘Afghanistan: Red Light at the Crossroads’, World Music Vol.2: The Rough Guide (Latin and North America, Caribbean, India, Asia and Pacific) (London: Rough Guides Ltd, 2000), 3–7

- www.zohra-music.org/ [The Zohra Ensemble’s official website, including background history, profiles, tour journal and videos: particularly moving to read and watch through at the present time.]

Latest Posts

Return to Finland: Rautavaara, Saariaho & Beyond

17th April 2024

Our previous visits to the music of Finland took us up to those composers born in the first decades of the 20th century, including Uuno Klami and Joonas Kokkonen. That generation brought Finnish music further away from its nationalist roots and the shadow of Sibelius, and closer to the modernism of the mid- and late 20th century. Now, on our final visit (at least for the time being), we look at two figures in particular who tackled some of modernism’s most advanced trends, and went beyond them to create outputs of... read more

read more

Classical Music: The Endgame?

10th April 2024

A recent visit to the London Coliseum brought home the scale of the challenge facing opera, not just at the home of the troubled English National Opera, but more generally – and, indeed, classical music more widely. What seemed to be a fairly respectable attandance was revealed – on a glance upwards to the upper circle and balcony – to be only half a house: the upper levels were completely empty, having been effectively closed from sale. And this on a Saturday evening! There was a time (in the 1970s and 80s) when... read more

read more

Artists in Focus: Masaaki Suzuki and the Bach Collegium Japan

3rd April 2024

Over the past three decades, the record catalogues have welcomed three landmark cycles of the complete Bach cantatas. John Eliot Gardiner’s survey of the complete sacred cantatas, made in a single year during his 2000 Bach Cantata Pilgrimage, grabbed most of the headlines. But the more long-term projects of Ton Koopman and Masaaki Suzuki (the latter with his Bach Collegium Japan) have their devotees, particularly among those who appreciate a more considered, patient approach in this music. Suzuki’s cycle in particular – the... read more

read more

Valete: Pollini, Eötvös & Janis

27th March 2024

The past fortnight has brought news of the deaths of three major figures from the post-war musical scene: two pianists and a composer-conductor.

Anyone who follows the classical music headlines even slightly will have learned of the death at the age of 82 of Maurizio Pollini. He was simply one of the greatest pianists of the post-war era. Born on 5 January 1942 in Milan, he was raised in a home environment rich in culture. His father Gino was a leading modern architect, his mother Renata Melotti a pianist, and her... read more

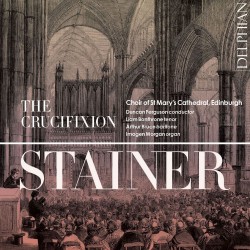

The Resurrection of Stainer’s ‘Crucifixion’

20th March 2024

Widely vilified as the epitome of mawkish late-Victorian religious sentimentality, John Stainer’s The Crucifixion was first performed in St Marylebone Parish Church on 24 February 1887 at the beginning of Lent. Composed as a Passion-themed work within the capabilities of parish choirs as part of the Anglo-Catholic revival, its publication by Novello led to its phenomenal success as churches throughout England quickly took it up. It also spawned many imitations – such as John Henry Maunder’s Olivet to Calvary – which lacked... read more

read more FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!