The Spin Doctor Europadisc's Weekly Column

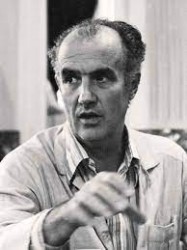

Celebrating Luigi Nono (1924-1990)

31st January 2024

31st January 2024

One of this year’s major musical anniversaries – the centenary of the birth of Luigi Nono on 29 January – has so far been little marked on the international scene. On the day itself, BBC Radio 3 broadcast none of his music (this week’s Composer of the Week is, instead, Stravinsky). A native of Venice, Nono was one of the leading figures of the post-war avant garde, and for many new music insiders his name ranks alongside those of Boulez and Stockhausen in the modernist Pantheon. Yet outside of his native Italy and the avant-garde hubs of Germany, his music is heard much less than it deserves.

One of this year’s major musical anniversaries – the centenary of the birth of Luigi Nono on 29 January – has so far been little marked on the international scene. On the day itself, BBC Radio 3 broadcast none of his music (this week’s Composer of the Week is, instead, Stravinsky). A native of Venice, Nono was one of the leading figures of the post-war avant garde, and for many new music insiders his name ranks alongside those of Boulez and Stockhausen in the modernist Pantheon. Yet outside of his native Italy and the avant-garde hubs of Germany, his music is heard much less than it deserves.This is partly no doubt due to his uncompromising political stance: active in the Resistance during the Nazi occupation, he quickly aligned himself and his music with the banner of Italian Marxism, and both Gramsci and Sartre were important later influences. Nono’s position set him apart from the pseudo-religious cosmology of Stockhausen, the more focused politicising of Boulez (aimed at establishing IRCAM at the Pompidou Centre in Paris), and the more accessible semiotic kleptomania of his compatriot Luciano Berio.

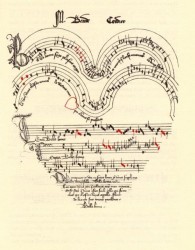

Nono’s origins were as Venetian as they come: born into a wealthy artistic family – his grandfather Luigi was a painter, his uncle Ernesto a sculptor – from 1943 to 1945 he studied composition with Gian Francesco Malipiero (another native of the city) at the Venice Conservatory, where he was introduced not just to the sacred polyphony and madrigals of the Italian Golden Age, but the music of Stravinsky, Bartók and the Second Viennese School as well. His encounter with the slightly older fellow-Venetian Bruno Maderna was crucial in fostering his interest in Schoenberg in particular, as were the 1948 conducting classes given by Hermann Scherchen in Venice in which both Nono and Maderna participated. Another key influence at this stage was the twelve-tone music of Luigi Dallapiccola, twenty years Nono’s senior.

But it was the serialism of Arnold Schoenberg that exerted the greatest pull on the young Nono. His breakthrough work was the Variazioni canoniche sulla serie dell’op.41 di Schönberg, first performed at that hotbed of musical modernism, Darmstadt. It was there that Nono attended classes given by another dominant modernist figure, Edgard Varèse. In 1953 he attended the posthumous world premiere of Schoenberg’s Moses und Aaron in Hamburg, where he met Schoenberg’s daughter Nuria: they married two years later. International recognition came with Nono’s cantata Il canto sospeso (1955–56), and by now he was regarded as a leading light in musical modernism. However, a very public falling out with Stockhausen came when the latter delivered a lecture pointedly criticising the text setting in this work, resulting in a robust response from Nono. The resulting estrangement lasted many years.

Nono’s operatic works are particularly celebrated, though he disdained the word ‘opera’ and all the baggage it entailed, preferring instead the term ‘azione scenica’ (scenic action). A landmark in this genre was Intolleranza 1960, whose themes of the plight of emigrants, working-class exploitation and political torture still feel astonishingly pertinent today. The 1960 Venice premiere caused a riot; a 2021 production from the Salzburg Festival conducted by Ingo Metzmacher (Blu-ray only) provides a timely opportunity for a reassessment of this vast and challenging work. Intolleranza 1960 can be seen as the culmination of Nono’s first ‘period’: in 1959 he delivered a controversial Darmstadt lecture in which he distanced himself from the then-fashionable use of chance in aleatoric music.

The 1960s and 70s saw Nono increasingly immersed in political causes, his works taking on a more polemical tone even as they embraced a more fractured, ‘punctual’ form of serialism. His ‘scenic action’ Al gran sole carico d'amore (1972–74), based on Brecht as well as texts by Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Marx and Lenin, dispensed with dramatic narrative to present crucial moments in the history of Communism. A visit to Moscow helped to awaken interest in modernism among such composers as Schnittke and Pärt. At the same time, Nono keenly embraced the use of tape and live electronics in his music. Como una ola de fuerza y luz (1972) for soprano, piano, large orchestra, tape and electronics, was written in memory of the Cuban revolutionary Luciano Cruz, and its premiere (conducted by ardent Nono champion Claudio Abbado) included Maurizio Pollini. At the other end of the scale, another work – composed specifically for Pollini - was the classic … sofferte onde serene … for piano and tape of 1976, whose carefully blended textures have made it something of a favourite among pianists and audiences committed to new music.

In Nono’s final decade, it was as if his music had become distilled to its bare essence: the textures and gestures sparser, the action in theatrical works non-existent, the focus on the act of listening itself, the experience immersive in a very different manner from the emerging minimalist fad, the musical language as uncompromising as ever, but attaining rare levels of beauty. Two works epitomise this ‘late’ phase: La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura for solo violin and eight tapes (1988) is an hour-long work which loops sounds back and presses the violin’s tone to extremes of quiet as well as scratchily loud, yet holds the listener spellbound over its course. Currently there are no fewer than three recordings to choose from.

But perhaps the crowning glory of Nono’s oeuvre is his vast Prometeo. Tragedia dell’ascolto of 1984. This ‘tragedy of listening’, a distillation of the Prometheus myth, employs texts by Hölderlin, Nietzsche, Rilke and Walter Benjamin, yet none of them intelligible to the ear; instead they are deployed by Nono and his librettist Massimo Cacciari as traces, parts of a mosaic whose designs constantly elude the listener while drawing them in. The performing forces are deployed around the audience – originally in an upturned ark within the church of San Lorenzo, Venice, where the work was premiered on 25 September 1984, conducted by Abbado. It was performed there again earlier this week, on the very anniversary of Nono’s birth: an entirely appropriate gesture for one of the city’s greatest sons, and a giant of musical modernism whose challenging works deserve to resonate down the generations. Ignore him at your peril!

Recommended recordings:

Intolleranza 1960 (Salzburg Festival / Metzmacher) 109457 (Blu-ray)

Lost in Venice with Prometheus (incl. ... sofferte onde serene ...) FUG716

La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura (Miranda Cuckson) UAV5992

Prometeo (cond. Marco Angius) STR37096

Latest Posts

‘In the black, dismal dungeon of despair’... Tackling music’s challenges

15th May 2024

Our column last week on ‘The Problem of Attracting Audiences’ prompted a typically thoughtful response from one of our regular readers, which in turn drew us to reflect further on this issue. The number of performers, critics and other commentators weighing into the current debate ought to persuade all but the most sceptical of followers that the arts in general, and classical music in particular, are currently facing a moment of real crisis. And even though there are plenty of other areas of the contemporary world that are... read more

read more

A Smart Move? The Problem of Attracting Audiences...

8th May 2024

Given the current funding crisis in the arts, classical music desperately needs to attract more audiences, in an ever more competitive marketplace. The attempts to woo younger and more diverse people to events have often been met with scorn by seasoned concertgoers. ‘Give it time,’ they say, ‘and people will become more interested in the classics as they get older.’ But time is running out for many arts organisations – choirs, orchestras, opera companies and smaller ensembles. And among potential audiences may be the... read more

read more

On Rhythm

1st May 2024

Of all the elements of music, one of the most fundamental is also the most difficult to pin down: rhythm. It’s something we think we understand (or at least can identify), until we start to think about it. The short definition in The Oxford English Dictionary is ‘a strong, regular, repeated pattern of sounds or movements’, while The New Harvard Dictionary of Music is more circumspect in defining it in brief as ‘The pattern of music in time’. Even if not marked by ‘strong, regular, repeated pattern[s] of sounds’, a piece of... read more

read more

Remembering Sir Andrew Davis

24th April 2024

The death at the age of 80 of the conductor Sir Andrew Davis has robbed British music of one of its most ardent champions. Since the announcement of his death this weekend, numerous headlines have linked him with his many appearances at the helm of the BBC’s Last Night of the Proms, occasions which were enlivened by his lightly-worn bonhomie and mischievous wit. The Last Night, with its succession of patriotic favourites, was something that came naturally to Davis, as did an easy rapport with both his fellow musicians and... read more

read more

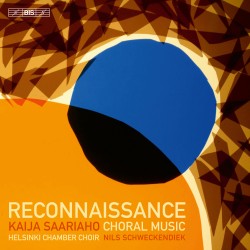

Return to Finland: Rautavaara, Saariaho & Beyond

17th April 2024

Our previous visits to the music of Finland took us up to those composers born in the first decades of the 20th century, including Uuno Klami and Joonas Kokkonen. That generation brought Finnish music further away from its nationalist roots and the shadow of Sibelius, and closer to the modernism of the mid- and late 20th century. Now, on our final visit (at least for the time being), we look at two figures in particular who tackled some of modernism’s most advanced trends, and went beyond them to create outputs of... read more

read more FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!