The Spin Doctor Europadisc's Weekly Column

A Smart Move? The Problem of Attracting Audiences...

8th May 2024

8th May 2024

Given the current funding crisis in the arts, classical music desperately needs to attract more audiences, in an ever more competitive marketplace. The attempts to woo younger and more diverse people to events have often been met with scorn by seasoned concertgoers. ‘Give it time,’ they say, ‘and people will become more interested in the classics as they get older.’ But time is running out for many arts organisations – choirs, orchestras, opera companies and smaller ensembles. And among potential audiences may be the performers of tomorrow: an ever-dwindling band, as provision for music education is cut in favour of increased funding for more ‘profitable’ subjects in applied sciences and economics.

Given the current funding crisis in the arts, classical music desperately needs to attract more audiences, in an ever more competitive marketplace. The attempts to woo younger and more diverse people to events have often been met with scorn by seasoned concertgoers. ‘Give it time,’ they say, ‘and people will become more interested in the classics as they get older.’ But time is running out for many arts organisations – choirs, orchestras, opera companies and smaller ensembles. And among potential audiences may be the performers of tomorrow: an ever-dwindling band, as provision for music education is cut in favour of increased funding for more ‘profitable’ subjects in applied sciences and economics.Education is, of course, key (as we’ve remarked before). But strategies for attracting wider audiences certainly need addressing. Every year, the old guard complain at the ‘dumbing down’ of the BBC Proms, or the attempts by some musicians to engage with a repertoire more likely to attract younger people. It’s easy to pooh-pooh the efforts of Lang Lang and Anna Lapwood (the ‘TikTok organist’), but if they succeed in drawing more diverse audiences to the genre they should be applauded.

Some strategies, however, can backfire. The recent, much-publicised attempts to ‘open up’ Symphony Hall in Birmingham have attracted wide derision. Audiences are encouraged to wear whatever they’re comfortable in (er, haven’t we be doing that for years?), bring their drinks into the auditorium (pity the poor souls who have to clear up the mess afterwards) and, most controversially, take photos and short videos during performances and then share them online. It’s this last invitation that has attracted most criticism, and quite rightly. As Ian Bostridge bravely stated during his performance of Britten’s Les Illuminations, it can be enormously distracting for performers to be greeted with a sea of smartphones (many of them with torchlights on) while you’re trying to perform.

It's distracting, too, for audience members who want to concentrate on the music and the performance. Did no-one think this through properly? At a time when the access of the very young to smartphones is being hotly debated, when there’s talk of them being banned in schools, and when many young people are actually turning to app-lite ‘dumb phones’ in an effort to remove some of the pressures and stresses of modern life, do we really want more smartphones turned on and filming during performances?

There may be a place for smartphones in some lighter settings. Gerard Hoffnung and Malcolm Arnold would surely have had a field-day with them. Yet they’d be the first to admit that such gadgetry, and the desperate marketing strategy that lies behind it, have no place in works where the performers’ and audience’s concentration is uppermost, whether it be Britten, Beethoven or Brahms. (Stephen Hough’s wonderfully tongue-in-cheek response to the prospect of performing Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto in Birmingham is well worth a look.)

There is now a whole generation or two who only seem to be able to view the world via the screens of their smartphones (and maybe you’re reading this on one right now), whose every morsel, from breakfast to cocktail hour to midnight snack has to be snapped and plastered over social media. But viewing something through a lens and actually experiencing it are two entirely different things. Like the apocryphal holidaymakers of yore who see everything through their viewfinders and miss out entirely on the bigger experience, we’re at risk of encouraging behaviours that will rob music of its unique power to move and engage us, in a misguided effort to generate more online ‘content’. There has to be a better way!

Perhaps the Nordic model has some answers: festivals of music where the distinctions between genres are blurred, where there’s a more relaxed approach to performances, and where the relationship between audiences and performers seems to be a far more fruitful and collegial one. Yet the nature of the Proms – both the length and scale of the festival and the size of its main venue – means that there are no easy answers. Cross-genre fertilisation (and the changing of attitudes that goes with it) takes generations, not a couple of months or years. Longer-term strategies, not a few cheap gimmicks, are needed. Earlier start times would help, as (paradoxically) would more late-night and even all-night performances, some in smaller venues. A more thoughtful, less sensationalist approach might not seem immediately attractive, but it could provide a longer-term answer.

One has some sympathy for those executives for whom the pressures of the job mean that they can rarely afford to think beyond next year’s potential audience figures and takings. Yet a wider vision is sorely needed, along with education, a long-term strategy for the arts, and performers who can communicate an enthusiasm for the genre. So, please, ditch the gimmicks (or at least think them through and consult with performers and audiences first!). Try to move away from the ‘Doctor Who + Star Wars + Mahler = cash’ model to something more fundamental and sustainable. Something that really will have audiences dropping their phones to live the experience. Change – even radical change – needs to be organic rather than imposed. Embrace it, certainly, but think it through before doing anything daft…

Your suggestions, please, on a postcard!

Latest Posts

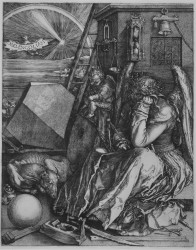

‘In the black, dismal dungeon of despair’... Tackling music’s challenges

15th May 2024

Our column last week on ‘The Problem of Attracting Audiences’ prompted a typically thoughtful response from one of our regular readers, which in turn drew us to reflect further on this issue. The number of performers, critics and other commentators weighing into the current debate ought to persuade all but the most sceptical of followers that the arts in general, and classical music in particular, are currently facing a moment of real crisis. And even though there are plenty of other areas of the contemporary world that are... read more

read more

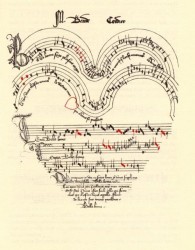

On Rhythm

1st May 2024

Of all the elements of music, one of the most fundamental is also the most difficult to pin down: rhythm. It’s something we think we understand (or at least can identify), until we start to think about it. The short definition in The Oxford English Dictionary is ‘a strong, regular, repeated pattern of sounds or movements’, while The New Harvard Dictionary of Music is more circumspect in defining it in brief as ‘The pattern of music in time’. Even if not marked by ‘strong, regular, repeated pattern[s] of sounds’, a piece of... read more

read more

Remembering Sir Andrew Davis

24th April 2024

The death at the age of 80 of the conductor Sir Andrew Davis has robbed British music of one of its most ardent champions. Since the announcement of his death this weekend, numerous headlines have linked him with his many appearances at the helm of the BBC’s Last Night of the Proms, occasions which were enlivened by his lightly-worn bonhomie and mischievous wit. The Last Night, with its succession of patriotic favourites, was something that came naturally to Davis, as did an easy rapport with both his fellow musicians and... read more

read more

Return to Finland: Rautavaara, Saariaho & Beyond

17th April 2024

Our previous visits to the music of Finland took us up to those composers born in the first decades of the 20th century, including Uuno Klami and Joonas Kokkonen. That generation brought Finnish music further away from its nationalist roots and the shadow of Sibelius, and closer to the modernism of the mid- and late 20th century. Now, on our final visit (at least for the time being), we look at two figures in particular who tackled some of modernism’s most advanced trends, and went beyond them to create outputs of... read more

read more

Classical Music: The Endgame?

10th April 2024

A recent visit to the London Coliseum brought home the scale of the challenge facing opera, not just at the home of the troubled English National Opera, but more generally – and, indeed, classical music more widely. What seemed to be a fairly respectable attandance was revealed – on a glance upwards to the upper circle and balcony – to be only half a house: the upper levels were completely empty, having been effectively closed from sale. And this on a Saturday evening! There was a time (in the 1970s and 80s) when... read more

read more FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!