The Spin Doctor Europadisc's Weekly Column

Proust and Music

6th July 2021

6th July 2021

The creative output of Marcel Proust – the 150th anniversary of whose birth falls this week – is drenched in the French culture of his time: La Belle Époque and the vibrant social and artistic atmosphere of turn-of-the-century Paris and its environs. Music plays a key part in Proust’s monumental seven-volume novel Ŕ la recherche du temps perdu (‘In Search of Lost Time’), above all in the enigmatic Sonata by the fictional composer Vinteuil, a phrase from which triggers an instance of ‘involuntary memory’ for one of the main characters, Charles Swann. (A similar example of triggered ‘involuntary memory’ forms one of the novels best-known passages, the episode of the madeleine.)

The creative output of Marcel Proust – the 150th anniversary of whose birth falls this week – is drenched in the French culture of his time: La Belle Époque and the vibrant social and artistic atmosphere of turn-of-the-century Paris and its environs. Music plays a key part in Proust’s monumental seven-volume novel Ŕ la recherche du temps perdu (‘In Search of Lost Time’), above all in the enigmatic Sonata by the fictional composer Vinteuil, a phrase from which triggers an instance of ‘involuntary memory’ for one of the main characters, Charles Swann. (A similar example of triggered ‘involuntary memory’ forms one of the novels best-known passages, the episode of the madeleine.)Proust was steeped in music from an early age, and his love affair and subsequent lifelong friendship with the composer Reynaldo Hahn only intensified his involvement with it. The salons and soirées of high-society Paris were as central to Proust’s life as they are to the fictional world of In Search of Lost Time, surveyed with a mixture of nostalgia and biting wit. The entertainments typically included music, and Proust was drawn in particular to music’s ability to act as a catalyst for exceptionally vivid memories. He was also a shrewd if sometimes biased judge of musical quality. Among his greatest enthusiasms was the music of Fauré: ‘I not only love, not only admire, not only adore your music, I have been and am still falling in love with it,’ he wrote to the composer in 1897. ‘I could write a book more than 300 pages long about it.’ About the other great musical figure of contemporary Paris, Saint-Saëns, Proust was more equivocal, admiring his complete naturalness and boundless facility while rather less ecstatic about the overall artistic quality. Nevertheless it is Saint-Saëns’s D minor Violin Sonata, op.75, that seems to have provided a model for Vinteuil’s Sonata in an early draft of the novel.

Inevitably Proust was enthusiastic about Hahn’s music – not just the songs for which he is now best remembered, but the stage works, including the musical comedies: neither Hahn nor Proust were at all snobbish about enjoying or engaging with music at the more popular end of the spectrum. Proust compared Hahn’s ability to portray ‘sadness, tenderness, assuagement before nature’ with that of Schumann, an indication of his catholic tastes, as is his deep admiration for Beethoven’s late quartets, which were still widely regarded as ‘challenging’ music at the time. When not feeling up to venturing out to the theatre or salon, Proust engaged musicians to come round to his cork-lined rooms at 102 Boulevard Haussmann to play for him while he lay down in the darkness. On one celebrated occasion in April 1916, at a very late hour he was ‘tormented by the desire to hear ... César Franck's quartet’, duly gathered the players up in a motor car, and had them play the work in his rooms while he listened in silence, opening his eyes at the end to request them to play it all again! In later years, Franck appears to have supplanted Fauré as Proust’s favourite composer, possibly because of the influence of Liszt and above all Wagner on the Belgian composer’s mature works.

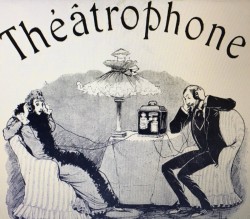

Like most cultured Parisians of the time, Proust was swept along by the wave of Wagnermania that had hit the French capital, and he seems to have been familiar with all of Wagner’s great operas, in particular Tristan, Meistersinger, Die Walküre and Parsifal, some of which he experienced in the theatre. Others he listened to via one of the most remarkable technological gadgets of the time, the théâtrophone, an early form of ‘live streaming’ by which listeners could enjoy theatre performances transmitted over telephone lines to a pair of earpieces in the comfort of their own homes! This is certainly how he listened (repeatedly!) to Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande from the Opéra-Comique in 1911, an experience which fed into the writing of volume 5 of In Search of Lost Time, Sodome et Gomorrhe. He knew enough about the wider repertoire to associate Pelléas’s emergence from the underground vault with the similar scene in Beethoven’s Fidelio. ‘The parts I like best are those in which there is music without words,’ he wrote to Hahn on 4 March 1911.

Proust’s musical knowledge was uncommonly wide, from Palestrina, Couperin, Rameau, Haydn and Mozart right up to the latest works of his compatriots, and by no means excluding the great figures of the 19th-century Austro-German ‘mainstream’. He was acutely sensitive to music’s light and shade, its limitless capacity for nuance, finesse and evocation beyond the power of words, which explains his fondness for Schumann and Fauré in particular, but also for late Beethoven. In his tastes he was more than merely a product of his times, however refined, often functioning more like a crucible for their ideas and experiences. His musical passions were decidedly fitful, however: at their most intense when they fed into his own work, while at other times pushed firmly to one side. Yet, like Proust’s greatest work, his tastes in music seem to capture the essence of an entire epoch, and for anyone at all interested in his output (whether or not they have the stamina, or indeed time, to read his magnum opus) they have the power to unlock a whole world.

Proust and Music: a few recommendations

- Proust: Le Concert retrouvé (Langlois de Swarte/Williencourt) HMM902508

- Music from Proust’s Salons (Isserlis/Shih) BIS2522

- La Sonate de Vinteuil (Maria & Nathalia Milstein) MIR384

- Hahn - Ô mon bel inconnu (Véronique Gens et al.) BZ1043

- Debussy - Pelléas et Mélisande (Janson, de los Angeles et al.) SBT3051

- Wagner - Overtures, Preludes & Arias (Cluytens et al.) SBT1256

Latest Posts

Remembering Sir Andrew Davis

24th April 2024

The death at the age of 80 of the conductor Sir Andrew Davis has robbed British music of one of its most ardent champions. Since the announcement of his death this weekend, numerous headlines have linked him with his many appearances at the helm of the BBC’s Last Night of the Proms, occasions which were enlivened by his lightly-worn bonhomie and mischievous wit. The Last Night, with its succession of patriotic favourites, was something that came naturally to Davis, as did an easy rapport with both his fellow musicians and... read more

read more

Return to Finland: Rautavaara, Saariaho & Beyond

17th April 2024

Our previous visits to the music of Finland took us up to those composers born in the first decades of the 20th century, including Uuno Klami and Joonas Kokkonen. That generation brought Finnish music further away from its nationalist roots and the shadow of Sibelius, and closer to the modernism of the mid- and late 20th century. Now, on our final visit (at least for the time being), we look at two figures in particular who tackled some of modernism’s most advanced trends, and went beyond them to create outputs of... read more

read more

Classical Music: The Endgame?

10th April 2024

A recent visit to the London Coliseum brought home the scale of the challenge facing opera, not just at the home of the troubled English National Opera, but more generally – and, indeed, classical music more widely. What seemed to be a fairly respectable attandance was revealed – on a glance upwards to the upper circle and balcony – to be only half a house: the upper levels were completely empty, having been effectively closed from sale. And this on a Saturday evening! There was a time (in the 1970s and 80s) when... read more

read more

Artists in Focus: Masaaki Suzuki and the Bach Collegium Japan

3rd April 2024

Over the past three decades, the record catalogues have welcomed three landmark cycles of the complete Bach cantatas. John Eliot Gardiner’s survey of the complete sacred cantatas, made in a single year during his 2000 Bach Cantata Pilgrimage, grabbed most of the headlines. But the more long-term projects of Ton Koopman and Masaaki Suzuki (the latter with his Bach Collegium Japan) have their devotees, particularly among those who appreciate a more considered, patient approach in this music. Suzuki’s cycle in particular – the... read more

read more

Valete: Pollini, Eötvös & Janis

27th March 2024

The past fortnight has brought news of the deaths of three major figures from the post-war musical scene: two pianists and a composer-conductor.

Anyone who follows the classical music headlines even slightly will have learned of the death at the age of 82 of Maurizio Pollini. He was simply one of the greatest pianists of the post-war era. Born on 5 January 1942 in Milan, he was raised in a home environment rich in culture. His father Gino was a leading modern architect, his mother Renata Melotti a pianist, and her... read more

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!