The Spin Doctor Europadisc's Weekly Column

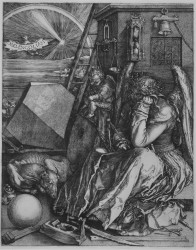

The Finnish Question: Before Sibelius

27th September 2023

27th September 2023

To appreciate the impact of the changes that came over Finnish music from the early 20th century onwards, one must delve into the country’s past. From the mid-13th century, the Finnish lands – including Lapland to the north, Ostrobothnia in the west and centre, and Karelia in the east – were under Swedish rule. Thus, while the Christianisation of the region dates back to at least the 11th century (with the first missions there rather earlier), the growing Swedish influence in the 12th century ensured that the form of Christianity was Catholic, with the monastic Dominican order playing a particularly dominant role. The Reformation was embraced during the 16th century in the form of Lutheranism (resulting in a proliferation of chorale books in both Swedish and Finnish). For many years, non-folk music was chiefly practised – as elsewhere across Europe – under the aegis of the church. Professional music first started with the building of church organs during the 17th century, and the need for trained musicians to play them and lead the musical side of the worship.

To appreciate the impact of the changes that came over Finnish music from the early 20th century onwards, one must delve into the country’s past. From the mid-13th century, the Finnish lands – including Lapland to the north, Ostrobothnia in the west and centre, and Karelia in the east – were under Swedish rule. Thus, while the Christianisation of the region dates back to at least the 11th century (with the first missions there rather earlier), the growing Swedish influence in the 12th century ensured that the form of Christianity was Catholic, with the monastic Dominican order playing a particularly dominant role. The Reformation was embraced during the 16th century in the form of Lutheranism (resulting in a proliferation of chorale books in both Swedish and Finnish). For many years, non-folk music was chiefly practised – as elsewhere across Europe – under the aegis of the church. Professional music first started with the building of church organs during the 17th century, and the need for trained musicians to play them and lead the musical side of the worship.It was in the 18th century that secular classical music-making really established itself, with the establishment of the collegium musicum at Turku University – Finland’s first orchestra – by the organist of Turku Cathedral, Carl Petter Lenning (1711–1788). During the enlightened rule of Gustav III (r. 1771–1792), the ‘Aurora’ secret society – established for the promotion of science, history and the arts – had its own orchestra which gave Finland’s first public concerts in the mid-1770s, and a further development was the setting up of the Turku Musical Society in 1790 for the express purpose of establishing an orchestra and mounting concerts.

Unsurprisingly, Finland’s first composer of real note – Bernhard Crusell (1775–1838) – was, although a native of south-western Finland, active chiefly in the Swedish capital Stockholm, where he was clarinettist in the court orchestra, and where he died five years after his retirement from playing. Crusell is remembered today for the fine chamber music and concertos he wrote for his own instrument (on which he became a celebrated soloist). Yet his other music includes many songs, an opera (The Little Slave Girl, 1824, fashionably set in the near East), and numerous other vocal works. Among these, the Viking-themed ‘Declamatorium’ The Last Warrior – recently recorded on the Ondine label – is a notable example of the new fashion for looking back to the legendary historical past and the idolisation of ancient times in raising national and cultural awareness. Its narrative elements – in particular the declaimed text – will appeal to anyone who loves the poetry of the Swedish language in, say, the films of Ingmar Bergman.

By the time Crusell wrote both The Little Slave Girl and The Last Warrior, his homeland had changed hands for the first time in nearly 600 years: as a result of Sweden’s defeat in the Finnish War of 1808–09, it was now part of the Russian Empire as the Grand Duchy of Finland. Nothing better illustrates the fluid nature of nations and allegiances of the era than that the anthem for the newly-autonomous Finland than that its eventual national anthem – Vårt land [‘Our country’] in Swedish, Maamme in Finnish – was composed (in the momentous year of 1848) by the Hamburg-born Fredrik Pacius (1809–1891). A pupil of Spohr, since 1834 he had taught at the University of Helsinki, and in 1838 had founded the Academic Male Voice Choir of Helsinki (Helsinki had replaced Turku as the Finnish capital in 1812). In 1852, in the spirit of Romantic nationalism, he composed the opera, Kung Karls jakt (King Charles’s Hunt), which – notwithstanding its Swedish libretto – was hailed as the first ‘Finnish opera’, and Pacius himself as the ‘Father of Finnish music’. Its only modern complete recording – issued on the Marco Polo label in 2004 – would be a welcome candidate for rerelease, if only for curiosity value. Essentially a Singspiel with substantial portions of dialogue (the adolescent king of the title is an exclusively spoken role), it owes much to the early German Romanticism of Weber, as do two further operas by Pacius, The Princess of Cyprus (1860) and Die Loreley (1862–87). The only completed movement of the composer’s Symphony in D minor (1850) is in a similar vein: all are eminent crowd-pleasers, but with little to hint at either a distinctive ‘Finnish’ style or an individual compositional style. Pacius’s choral works, which include a number of folk-song arrangements, are more suggestive, part of the pan-European boom in music for the thriving amateur choral society movement which raised national cultural awareness during the 19th century.

Pacius wasn’t alone in attempting to tackle national-themed subjects in a fundamentally Germanic style. The enticingly titled Kullervo Overture (1860) by Filip von Schantz (1835–1865) is rather slicker than the expectations aroused by its mythical theme; it was written after three years of study in the musical capital of 19th-century Europe, Leipzig, for the opening of a new building for Helsinki’s New Theatre, where Schantz was music director for three years. Yet the (bardic?) harp swirls amid the sombre strings and brass of its slow introduction, which returns to close the piece, hint at a composer of real talent, and one is left wondering how he might have impacted upon the development of Finnish music had lived beyond the age of just 30.

As it is, the composer who dragged Finnish music into the late 19th century was another, rather younger graduate of the Leipzig Conservatoire: Robert Kajanus (1856–1933). It was Kajanus’s fascination with Finnish folk legends – as repackaged in the seminal Kalevala (first published in 1835/36, enlarged 1849) – that in turn fired the imagination of his younger friend Jean Sibelius. As founder of Finland’s first professional orchestra, the Helsinki Orchestral Society (1882), Kajanus occupies a key place in Finnish musical life. Later he would become one of Sibelius’s most significant early champions. His own music lacks that final spark of genius that marks the latter’s works. Yet in pieces like Kullervo’s Funeral March (1880) with its ominously percussive opening and expressive use of the tenor register as well as string tremolandi, and still more the symphonic poem Aino (1885) culminating in the incorporation of a male chorus, he opened up a sense of space that would prove crucial to the Finnish musical revolution, and the voice of nature itself. If one is seeking the roots of modern Finnish music, a strong case can be argued for Kajanus as spiritual father-figure; no-one interested in its subsequent development can afford to ignore him.

Next time: Sibelius!

Recommended recordings:

Crusell - The Last Warrior (Helsinki Baroque Orchestra / Hakkinen) ODE14242

Pacius - Hymn to Finland: Choral Works (Akademiska Sangforeningen / Wikström) BISCD1694

Kajanus - Orchestral Works (Lahti Symphony Orchestra / Vänskä) BISCD1223

Latest Posts

‘In the black, dismal dungeon of despair’... Tackling music’s challenges

15th May 2024

Our column last week on ‘The Problem of Attracting Audiences’ prompted a typically thoughtful response from one of our regular readers, which in turn drew us to reflect further on this issue. The number of performers, critics and other commentators weighing into the current debate ought to persuade all but the most sceptical of followers that the arts in general, and classical music in particular, are currently facing a moment of real crisis. And even though there are plenty of other areas of the contemporary world that are... read more

read more

A Smart Move? The Problem of Attracting Audiences...

8th May 2024

Given the current funding crisis in the arts, classical music desperately needs to attract more audiences, in an ever more competitive marketplace. The attempts to woo younger and more diverse people to events have often been met with scorn by seasoned concertgoers. ‘Give it time,’ they say, ‘and people will become more interested in the classics as they get older.’ But time is running out for many arts organisations – choirs, orchestras, opera companies and smaller ensembles. And among potential audiences may be the... read more

read more

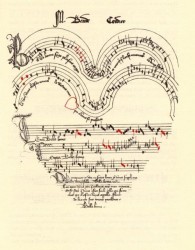

On Rhythm

1st May 2024

Of all the elements of music, one of the most fundamental is also the most difficult to pin down: rhythm. It’s something we think we understand (or at least can identify), until we start to think about it. The short definition in The Oxford English Dictionary is ‘a strong, regular, repeated pattern of sounds or movements’, while The New Harvard Dictionary of Music is more circumspect in defining it in brief as ‘The pattern of music in time’. Even if not marked by ‘strong, regular, repeated pattern[s] of sounds’, a piece of... read more

read more

Remembering Sir Andrew Davis

24th April 2024

The death at the age of 80 of the conductor Sir Andrew Davis has robbed British music of one of its most ardent champions. Since the announcement of his death this weekend, numerous headlines have linked him with his many appearances at the helm of the BBC’s Last Night of the Proms, occasions which were enlivened by his lightly-worn bonhomie and mischievous wit. The Last Night, with its succession of patriotic favourites, was something that came naturally to Davis, as did an easy rapport with both his fellow musicians and... read more

read more

Return to Finland: Rautavaara, Saariaho & Beyond

17th April 2024

Our previous visits to the music of Finland took us up to those composers born in the first decades of the 20th century, including Uuno Klami and Joonas Kokkonen. That generation brought Finnish music further away from its nationalist roots and the shadow of Sibelius, and closer to the modernism of the mid- and late 20th century. Now, on our final visit (at least for the time being), we look at two figures in particular who tackled some of modernism’s most advanced trends, and went beyond them to create outputs of... read more

read more FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!