The Spin Doctor Europadisc's Weekly Column

The Misfits (Part 2 of 2)

1st June 2021

1st June 2021

By the dawn of the twentieth century, the growth of western art music (what we refer to today under the broad umbrella term of ‘classical music’) both as creative phenomenon and as a society activity had grown enormously compared with a century earlier. Musical and wider cultural and social change – the expansion of urban populations, the growing need for cultural engagement of various sorts – were inextricably linked. And with this growth came an increase in the number of musical ‘outsiders’, who didn’t fit altogether neatly into the fashions or ‘-isms’ of the times. (The twentieth century became a century of ‘-isms’: expressionism, impressionism, symbolism, atonalism, serialism, modernism, postmodernism, etc.)

By the dawn of the twentieth century, the growth of western art music (what we refer to today under the broad umbrella term of ‘classical music’) both as creative phenomenon and as a society activity had grown enormously compared with a century earlier. Musical and wider cultural and social change – the expansion of urban populations, the growing need for cultural engagement of various sorts – were inextricably linked. And with this growth came an increase in the number of musical ‘outsiders’, who didn’t fit altogether neatly into the fashions or ‘-isms’ of the times. (The twentieth century became a century of ‘-isms’: expressionism, impressionism, symbolism, atonalism, serialism, modernism, postmodernism, etc.)One of the century’s most notable early misfits was Leoš Janáček: born in the middle of the nineteenth century, on the margins of the Austro-Hungarian empire, even by the time he came to prominence in his 60s and 70s, he was still regarded as a marginal figure, a Brno-based Moravian, in the Prague-centric circles of the Czech musical world. His distinctive personal style, forged gradually and only fully achieved by the late 1910s, was both unconventional and inimitable: though he had many students, none of their music sounds remotely like his, and his musical quirkiness was regarded by some as plain incompetent, by others as primitive, backward-looking, or at best of marginal interest. Only some four decades after his death in 1928 did he begin to be appreciated as one of the most original and powerful voices in twentieth-century music, and opera in particular.

Of other composers whose music forged prophetic yet highly individual new paths into the twentieth century, among the most intriguing is the Russian Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915), a musical prodigy whose early work developed the tradition of the Chopinesque miniature, but his interest in theosophical mysticism and his acutely-developed sense of synaesthesia (colour-association) led to a mature style of increasingly rich and sophisticated harmonic language that tested the limits of tonality (quite independently of what was going on in Schoenberg’s Vienna), while remaining intensely personal and visionary. His piano sonatas in particular trace an extraordinary stylistic journey, not least in the late White and Black Mass sonatas, while the later symphonies (The Divine Poem, The Poem of Ecstasy and Prometheus: The Poem of Fire) illustrate the ambitious vistas of his personal vision.

Further west, the Normandy-born but Parisian-raised Erik Satie (1866-1925) was an eccentric figure whose reputation was established with his proto-minimalist piano miniatures, the Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes for which he is still most famous. Forced by financial circumstances to work as a pianist in Parisian cabaret-cafes, he embraced the dawn of the jazz age, and worked on a variety of projects with Cubists, Dadaists and Surrealists. His most famous such work is the ballet Parade (1917), a collaboration with Cocteau, Diaghilev, Picasso and Massine set in the milieu of the Parisian music-hall: its riotous premiere and ensuing scandal saw Satie jailed for eight days after branding one critic ‘an arse’. Yet his most intriguing work is Vexations of 1893, a fourfold repetition of a theme apparently for piano, with the instruction that it should be played 840 times. Its posthumous premiere in September 1963, a marathon event organised by John Cage, and including among the relay of pianists such figures as David Tudor, Christian Wolff, David Del Tredici and Joshua Rifkin, was hugely influential on the post-war avant-garde. Though Satie was fortunate to find a receptive milieu in Parisian artistic circles, in many ways his strikingly enigmatic and elusive music was years ahead of its time, its circles and obsessions inextricably bound up with his personal eccentricities.

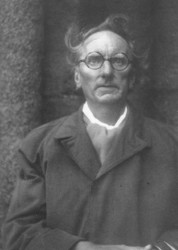

In northern Europe there was another composer whose music was similarly ahead of its time, yet who remained on the margins even in his native Denmark. Rued Langgaard (1893-1952, pictured above) spent most of his life trying to obtain a position as a church organist, something he only eventually achieved at the age of 46. Stylistically he owed much to Wagner and Richard Strauss, with a similarly superb gift at orchestration. His symphonies, however, are often visionary, and his perhaps his greatest work, the vast Music of the Spheres, calls for large orchestra, chorus, offstage orchestra and soprano soloist, with an organ and a piano whose strings are struck directly by the player, rather than via the usual keyboard and hammer. The work’s use of string clusters later earned the admiration of György Ligeti, himself one of the twentieth century’s great individualists, who achieved the sort of contemporary acclaim that Langgaard could only have dreamt of. Langgaard left a vast output, including sixteen symphonies and six string quartets, much of which has still to be more widely discovered.

Across the Atlantic, many North American composers had more success in winning exposure in a cultural climate that was still searching for its own distinctively American voice. But Charles Ives (1874-1954), an experimentalist whose work embraced polytonality, polyrhythms, quarter tones and tone clusters, was another figure to whom full recognition came only posthumously. Works such as Central Park in the Dark (1906), The Unanswered Question (1908) and Three Places in New England (1911-14) incorporate a kind of hyper-Mahlerian layering of materials, often including popular tunes in otherwise densely chromatic contexts, which make Ives’s among the most distinctive American music of the first half of the century, much admired by such modernist figures as Henry Cowell and Elliott Carter. Two other composers stand out from the mainstream: firstly, self-proclaimed ‘bad boy’ George Antheil (1900-1959), whose Ballet mécanique (1924), originally designed as an accompaniment to the Dadaist film of the same name, incorporated mechanical instruments such as player pianos an aeroplane propellors, reflecting the increasing mechanisation of contemporary society. Secondly, there is the French émigré Edgard Varčse (1883-1965), whose avant-garde masterpieces from Amériques, Intégrales, Arcana and Ionsiation to Déserts make use of unconventional forces, notably enlarged percussion and, in later works, pioneering use of electronic tape. International recognition came late, but Varčse was a key influence on the European and American post-war avant-garde, while retaining a unique soundworld that makes his music unmistakable.

No survey of musical misfits would be complete without at least passing reference to two more figures from the anglophone world: Australian composer-pianist Percy Grainger (1882-1961), whose innovative, unorthodox style played a crucial if unlikely role in the use of folk-song as a source of creative renewal, and the reclusive Kaikhosru Sorabji (1892-1988), whose phenomenally demanding piano works (including the 4-hour Opus clavicembalisticum of 1930) show the unmistakable influence of Scriabin and Busoni, but taken to ever greater extremes.

The multiplicity of distinctive individual voices in contemporary music continues to this day, a reflection of society’s growing pluralism and diversity, but the above composers are among the most striking originals whose music can continue to surprise and fascinate us to this day.

A few recommended recordings (click on catalogue number for link to product page):

Janáček - The Diary of One Who Disappeared, Říkadla, etc. CDA68282

- Nicky Spence (tenor), Julius Drake (piano) et al.

Two of Janáček’s most distinctive works, together with a selection of his folk-song settings

Scriabin - Complete Piano Sonatas CDA671312

- Marc-André Hamelin (piano)

Tout Satie!: Erik Satie Complete Edition 2564604796

- A comprehensive 10-disc survey at an attractive price

Langgaard - Symphonies 2 & 6 6220653

- Wiener Philharmoniker, Sakari Oramo

Superbly idiomatic performances that emphasise the music’s Straussian opulence

Ives - Three Places in New England, Central Park in the Dark, etc. CHSA5163

- Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, Andrew Davis

Antheil - Symphony no.1, Capital of the World, etc. CHAN20080

- BBC Philharmonic, John Storgĺrds

Varčse - Amériques, Offrandes, Offrandes, Arcana, Déserts, etc. 2564620872

- Orchestre National de France, Kent Nagano

Percy Grainger Favourites ALC1410

- Eastman-Rochester Wind Ensemble & Pops Orchestra, Frederick Fennell

Sorabji - Opus clavicembalisticum BISCD106264

- Geoffrey Douglas Madge (piano)

Latest Posts

Remembering Sir Andrew Davis

24th April 2024

The death at the age of 80 of the conductor Sir Andrew Davis has robbed British music of one of its most ardent champions. Since the announcement of his death this weekend, numerous headlines have linked him with his many appearances at the helm of the BBC’s Last Night of the Proms, occasions which were enlivened by his lightly-worn bonhomie and mischievous wit. The Last Night, with its succession of patriotic favourites, was something that came naturally to Davis, as did an easy rapport with both his fellow musicians and... read more

read more

Return to Finland: Rautavaara, Saariaho & Beyond

17th April 2024

Our previous visits to the music of Finland took us up to those composers born in the first decades of the 20th century, including Uuno Klami and Joonas Kokkonen. That generation brought Finnish music further away from its nationalist roots and the shadow of Sibelius, and closer to the modernism of the mid- and late 20th century. Now, on our final visit (at least for the time being), we look at two figures in particular who tackled some of modernism’s most advanced trends, and went beyond them to create outputs of... read more

read more

Classical Music: The Endgame?

10th April 2024

A recent visit to the London Coliseum brought home the scale of the challenge facing opera, not just at the home of the troubled English National Opera, but more generally – and, indeed, classical music more widely. What seemed to be a fairly respectable attandance was revealed – on a glance upwards to the upper circle and balcony – to be only half a house: the upper levels were completely empty, having been effectively closed from sale. And this on a Saturday evening! There was a time (in the 1970s and 80s) when... read more

read more

Artists in Focus: Masaaki Suzuki and the Bach Collegium Japan

3rd April 2024

Over the past three decades, the record catalogues have welcomed three landmark cycles of the complete Bach cantatas. John Eliot Gardiner’s survey of the complete sacred cantatas, made in a single year during his 2000 Bach Cantata Pilgrimage, grabbed most of the headlines. But the more long-term projects of Ton Koopman and Masaaki Suzuki (the latter with his Bach Collegium Japan) have their devotees, particularly among those who appreciate a more considered, patient approach in this music. Suzuki’s cycle in particular – the... read more

read more

Valete: Pollini, Eötvös & Janis

27th March 2024

The past fortnight has brought news of the deaths of three major figures from the post-war musical scene: two pianists and a composer-conductor.

Anyone who follows the classical music headlines even slightly will have learned of the death at the age of 82 of Maurizio Pollini. He was simply one of the greatest pianists of the post-war era. Born on 5 January 1942 in Milan, he was raised in a home environment rich in culture. His father Gino was a leading modern architect, his mother Renata Melotti a pianist, and her... read more

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!