The Spin Doctor Europadisc's Weekly Column

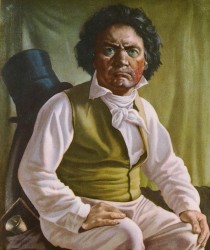

A shopping list by Beethoven... (or Breaking away from the Age of the Statue)

22nd September 2021

22nd September 2021

+ Spice.

+ Wine.

+ Macaroni.

+ Tooth powder.

The obsession with composers’ appearances and lives has cast long shadows over their output. It is almost impossible to engage in discussion of Beethoven’s music without mention of his deafness, or the personal crisis that resulted in the ‘Heiligenstadt Testament’, or the identity of his ‘Immortal Beloved’, or his hero-worship (culminating in profound disillusionment) of Napoleon Bonaparte. With Shostakovich, it’s his recurring victimisation at the hands of the Soviet regime (and the veracity of the posthumously published Testimony) that overshadows the music, with Tchaikovsky his catastrophic marriage and battles with ‘Fate’, with Janáček his ‘muse’ Kamila Stösslová (not to mention his immersion in folk and speech melodies), with Schubert his sexuality, and so on… All these biographical details (some rooted loosely in fact, others more conjectural) form pegs from which to hang the musical works, denying the latter a life of their own.

No doubt this situation is the result of our need for ‘heroes’ or role-models, for exemplars of artistic achievement. And evidence for this is to be found not just among the ranks of composers (whom we still tend to divide into the ‘great’ and the second- (or third, or fifth-) rate. Performers are similarly lionised (think of Callas, Gould, Furtwängler…), with lesser mortals continually compared to the greats. Our eagerness to discover the greatest performances (the ‘Building a Library’ choices, if you will) is a regular reminder of this need to situate composers and their works, musicians and their performances, in the Pantheon of the Greats.

An alternative approach would be to talk about music itself – the sounding phenomenon in its various guises, from live performance and recording to the printed or manuscript score – in an intelligent and intelligible way. This is easier said than done. In the Good Old Days, programme notes went into great detail describing a work’s themes and forms, and readers were assumed to be familiar with such concepts as sonata or variation form, exposition, development and recapitulation, first and second subjects, tonic, dominant and relative major keys. How much did this tell them about the music? In rare cases, quite a lot, but usually very little indeed, short of providing a few markers to be ticked off as the performance proceeded.

More recently, the old positivist approach has been replaced by the enthusing commentary, with ever more gushing pronouncements about how amazing or extraordinary this or that work, composer, artist or performance is, until the poor listener goes into sensory overload under a surfeit of adjectives. Much (perhaps too much) depends on how and individual listener or reader responds to the style and personality of a particular commentator, although the latter’s skill in deploying pertinent illustrative examples (if only to give the poor listener a break from the constant flow of superlatives) will also be a factor.

There have, on occasion, been approaches that have tried to avoid verbiage altogether. Hans Keller’s ‘wordless functional analyses’, some of them broadcast in the 1950s and 60s, constituted one such attempt, though Keller’s failure to present a fully supportive methodology meant that this interesting project didn’t get much further, and the analyses he did produce were largely restricted to the established canon of Bach, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. More fruitful in terms of range were the graphic analyses of Heinrich Schenker (recently the object of sustained criticism, but still highly influential), yet their score-based idiom, with notation and concepts that often baffle even the musically-literate, and a similar restriction to the canonical composers of the western tonal tradition (overwhelmingly though not exclusively Austro-German), present similar obstacles.

Finding a mode of communication even remotely worthy of the task of discussing music in all its infinite complexity while remaining intelligible is no easy task. Yet this should not stop us trying. To wrest music away from the clutches of music-as-biography (a mere soundtrack to the life of its creators) is a legitimate and still much-needed objective. It requires, on the one hand, a broader contextualisation of the music within its social, cultural, aesthetic, political and religious surroundings, reaching far beyond the limits of a particular composer’s biographical inventory. There is a growing body of work that attempts to address precisely these issues (for example, the excellent Cambridge Companion series), but it remains largely in the academic domain, often aimed at fellow academics (and correspondingly pricey), and is rarely heard through the din of the biographical myth-spinners and gushing enthusiasts.

Latest Posts

Remembering Sir Andrew Davis

24th April 2024

The death at the age of 80 of the conductor Sir Andrew Davis has robbed British music of one of its most ardent champions. Since the announcement of his death this weekend, numerous headlines have linked him with his many appearances at the helm of the BBC’s Last Night of the Proms, occasions which were enlivened by his lightly-worn bonhomie and mischievous wit. The Last Night, with its succession of patriotic favourites, was something that came naturally to Davis, as did an easy rapport with both his fellow musicians and... read more

read more

Return to Finland: Rautavaara, Saariaho & Beyond

17th April 2024

Our previous visits to the music of Finland took us up to those composers born in the first decades of the 20th century, including Uuno Klami and Joonas Kokkonen. That generation brought Finnish music further away from its nationalist roots and the shadow of Sibelius, and closer to the modernism of the mid- and late 20th century. Now, on our final visit (at least for the time being), we look at two figures in particular who tackled some of modernism’s most advanced trends, and went beyond them to create outputs of... read more

read more

Classical Music: The Endgame?

10th April 2024

A recent visit to the London Coliseum brought home the scale of the challenge facing opera, not just at the home of the troubled English National Opera, but more generally – and, indeed, classical music more widely. What seemed to be a fairly respectable attandance was revealed – on a glance upwards to the upper circle and balcony – to be only half a house: the upper levels were completely empty, having been effectively closed from sale. And this on a Saturday evening! There was a time (in the 1970s and 80s) when... read more

read more

Artists in Focus: Masaaki Suzuki and the Bach Collegium Japan

3rd April 2024

Over the past three decades, the record catalogues have welcomed three landmark cycles of the complete Bach cantatas. John Eliot Gardiner’s survey of the complete sacred cantatas, made in a single year during his 2000 Bach Cantata Pilgrimage, grabbed most of the headlines. But the more long-term projects of Ton Koopman and Masaaki Suzuki (the latter with his Bach Collegium Japan) have their devotees, particularly among those who appreciate a more considered, patient approach in this music. Suzuki’s cycle in particular – the... read more

read more

Valete: Pollini, Eötvös & Janis

27th March 2024

The past fortnight has brought news of the deaths of three major figures from the post-war musical scene: two pianists and a composer-conductor.

Anyone who follows the classical music headlines even slightly will have learned of the death at the age of 82 of Maurizio Pollini. He was simply one of the greatest pianists of the post-war era. Born on 5 January 1942 in Milan, he was raised in a home environment rich in culture. His father Gino was a leading modern architect, his mother Renata Melotti a pianist, and her... read more

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!

FREE UK SHIPPING OVER £30!